Corticosteroids: To Taper or Not to Taper

Clinical judgment appears especially crucial when evaluating a patient’s risk of glucocorticoid-induced adrenal insufficiency

When this article comes out, I’ll be in the middle of the fourth week of my hospital Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience (APPE) at Christian Northeast Hospital within the BJC network. Firstly, I have been having an absolute blast working through clinical cases with my preceptor and other members of the healthcare team as we strive to provide the best possible care for our patients.

A recent discussion among the clinical pharmacists led to my first project, a drug information request exploring when to implement a corticosteroid taper to prevent adrenal insufficiency, specifically when treatment algorithms don't already have them built in. Initially, I took a step back to refresh myself on normal adrenal physiology and gain an understanding of what exactly adrenal insufficiency is! 😄

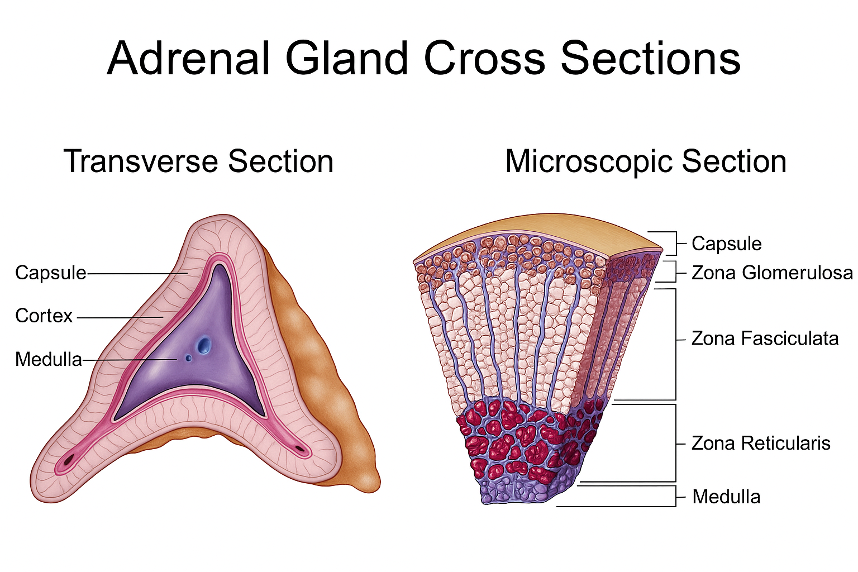

The adrenal gland is an integral component of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, with roles ranging from anti-inflammatory effects to regulating electrolytes and blood pressure. Its hormone production is organized by layer within the adrenal cortex, as well as in the adrenal medulla, as shown below:

→ Zona Glomerulosa – mineralocorticoids (e.g., aldosterone)

→ Zona Fasciculata – glucocorticoids (e.g., cortisol)

→ Zona Reticularis – androgens (e.g., DHEA)

→ Adrenal Medulla – catecholamines (e.g., epinephrine, norepinephrine)

Glucocorticoids like cortisol are most relevant for our topic today, since our steroid medications mimic their anti-inflammatory properties. These hormones act on nuclear receptors within cells to modulate genetic expression to decrease inflammation, enhance glucose availability, and regulate immune responses, among other effects (see our earlier article on nuclear receptors for a primer!).

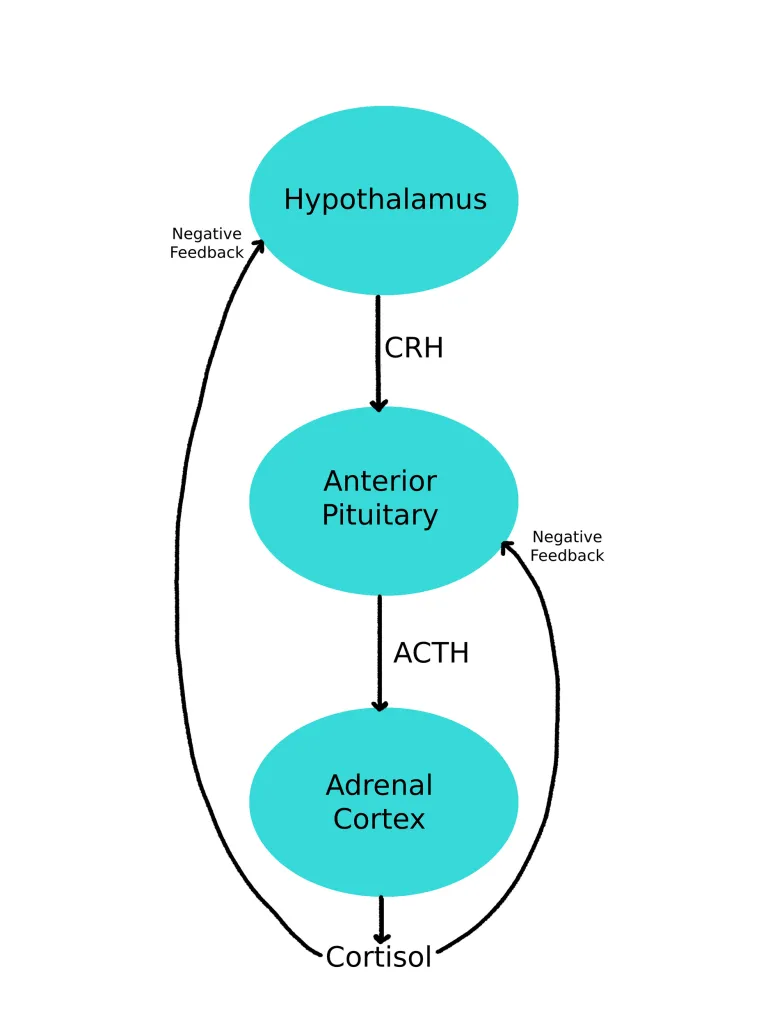

Normally, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which stimulates the anterior pituitary to produce adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH then prompts the adrenal glands to release cortisol. Increasing cortisol levels communicate with the hypothalamus and pituitary glands, signaling them to reduce CRH and ACTH production – a classic negative feedback loop!

Corticosteroids like prednisone and dexamethasone mimic these glucocorticoid effects but also suppress the HPA axis through the same negative feedback mechanism. With higher-than-physiologic doses given over long periods of time, the body decreases its production of cortisol. Abruptly stopping steroid medications in a state of minimal endogenous cortisol production can lead to adrenal insufficiency, presenting with symptoms such as fatigue, appetite suppression, weight loss (or a lack of weight gain in children), abdominal pain, and muscle or joint aches most commonly.

This brings us back to the drug information question: When should a steroid taper be used to prevent glucocorticoid-induced adrenal insufficiency? Unfortunately, the answer is not as straightforward as I would have liked.

The 2024 European Society of Endocrinology and Endocrine Society Joint Clinical Guideline for Glucocorticoid-Induced Adrenal Insufficiency does not recommend tapering for patients on short-term glucocorticoid therapy (<3–4 weeks), regardless of dose. However, this recommendation is labeled as very low-quality evidence.

These recommendations surprised me, as I imagined that a patient taking 60 mg/day of prednisone for 2 weeks could potentially be at a greater risk of adrenal insufficiency when compared to a patient taking 5 mg/day for 4 weeks. There are plenty of case reports of glucocorticoid-induced adrenal insufficiency at all doses and even in shorter treatment timeframes, including just a few days of therapy.

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis sought to define adrenal insufficiency incidence by route of administration, dose, and duration of therapy, among other things. Dose and duration were assessed specifically in asthmatic patients for the sake of homogeneity. This makes sense to me, as someone with a chronic malignancy would be immunocompromised and would likely require more intensive management when compared to other patient populations.

- By route: higher risk with intra-articular (52.2%) and oral (48.7%) glucocorticoids; lower risk with nasal (4.2%).

- By dose (asthmatic patients): adrenal insufficiency occurred in 2.4% (low dose) and 21.5% (high dose).

- By treatment duration (asthmatic patients): incidence was 1.4% (<28 days) and 27.4% (>12 months).

Overall, my conclusions were… mildly inconclusive 😅. Clinical judgment appears especially crucial when evaluating a patient’s risk of glucocorticoid-induced adrenal insufficiency, with factors such as older age, obesity, drug interactions (CYP3A4 inhibitors), and comorbidities all being weighed alongside the dose and duration used.

In my own opinion, I would most likely still recommend a steroid taper if my patient had been taking 60 mg/day of prednisone over 10 days, but potentially not in a patient taking 5 mg/day for 2-3 weeks, assuming no additional risk factors are present. Regardless, patients should always be counseled on the signs and symptoms of adrenal insufficiency so they know when to seek additional care if needed! What do you think?

*Information presented on RxTeach does not represent the opinion of any specific company, organization, or team other than the authors themselves. No patient-provider relationship is created.

References:

1. Felix Beuschlein, Et al. European Society of Endocrinology and Endocrine Society Joint Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Therapy of Glucocorticoid-induced Adrenal Insufficiency, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 109, Issue 7, July 2024, Pages 1657–1683, https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgae250

2. Broersen LH, Pereira AM, Jørgensen JO, Dekkers OM. Adrenal Insufficiency in Corticosteroids Use: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(6):2171-2180. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-1218