Essential Thrombocythemia

Essential thrombocythemia (ET) is a chronic BCR::ABL1-negative myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) defined by sustained thrombocytosis due to clonal megakaryocyte proliferation.

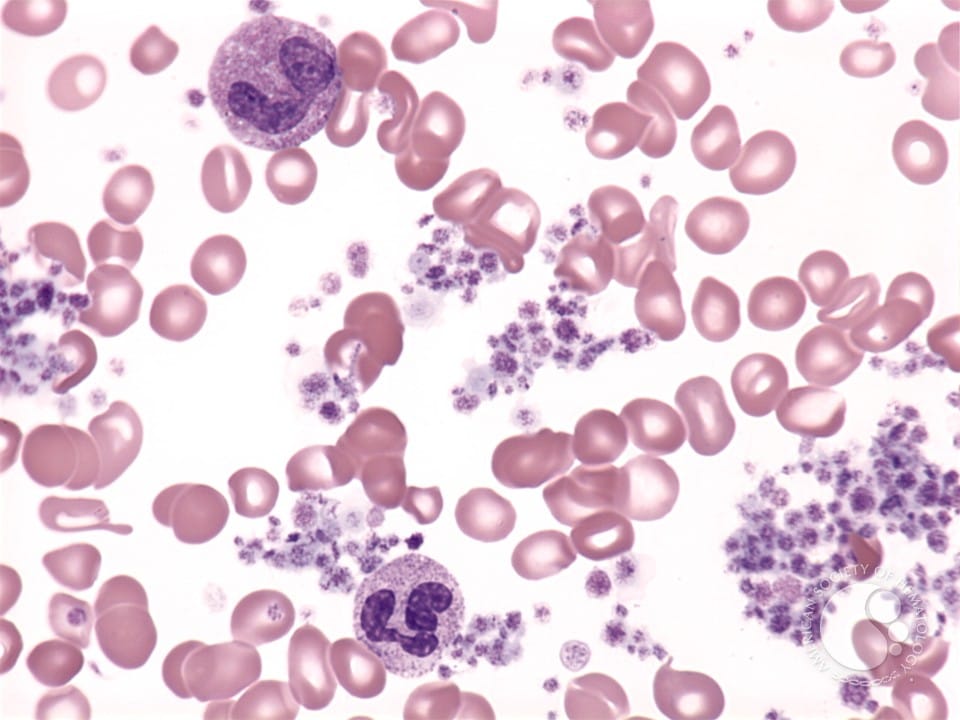

Essential thrombocythemia (ET) is a chronic BCR::ABL1-negative myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) defined by sustained thrombocytosis due to clonal megakaryocyte proliferation. ET most commonly presents in adults (median age ~60 years) and is associated with an increased risk of arterial and venous thrombosis, bleeding (paradoxically, especially with extreme thrombocytosis and acquired von Willebrand syndrome), and potential progression to myelofibrosis (MF) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Within 10 years, ~4% of patients will progress to MF, and ~1.4% will progress to AML.

The prevalence and incidence rates are ~50 and ~2 cases/100,000 people, respectively. While the life expectancy is often near-normal for low-risk patients (median survival 15-20 years), it can be shortened in those with thrombotic complications or disease transformation.1,2

Pathophysiology:2

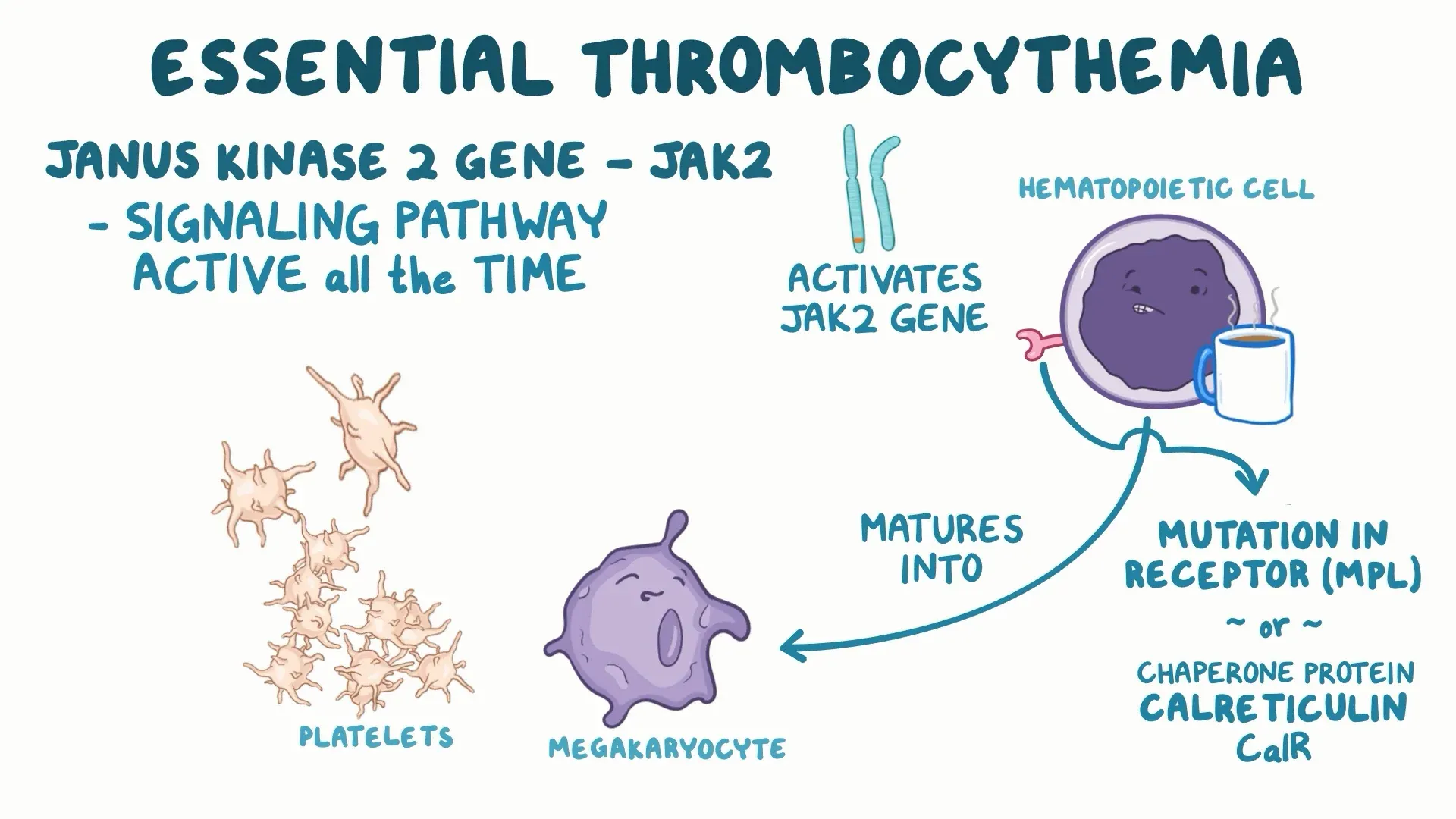

- Driver mutations:

- ~50% of ET cases harbor Janus Kinase (JAK)2 V617F

- ~25% carry calreticulin (CALR) mutations

- ~5% have myeloproliferative leukemia virus oncogene (MPL) mutations

- A minority are “triple-negative”

- These mutations activate JAK–STAT signaling, promoting megakaryocyte proliferation and increased platelet production. Mutation type influences clinical phenotype (e.g., JAK2-mutated patients have higher thrombotic risk; CALR-mutated patients often have higher platelet counts but lower thrombosis risk)

- Clonal heterogeneity & additional mutations:

- Additional somatic variants (e.g., SH2B3, U2AF1, TP53, IDH2) can influence prognosis and risk of fibrotic or leukemic transformation

Risk factors:3

- International Prognostic Score for ET (IPSET-Thrombosis):

- Age, prior thrombosis, JAK2 mutation status, and cardiovascular risk factors

- Very low:

- Age <60 years

- No thrombosis history

- JAK2/MPL unmutated

- Low:

- Age <60 years

- No thrombosis history

- JAK2/MPL mutated

- Intermediate:

- Age >60 years

- No thrombosis history

- JAK2/MPL unmutated

- High:

- Thrombosis history or

- Age >60 years with JAK2/MPL mutation

- Very low:

- Age, prior thrombosis, JAK2 mutation status, and cardiovascular risk factors

Diagnosis:4

The 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) diagnostic criteria requires either all 4 major OR the first 3 major and the minor:

- Major:

- Platelet count ≥450 × 109/L, plus

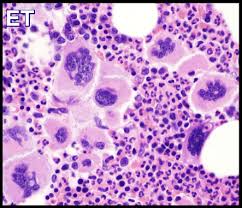

- Bone marrow biopsy showing proliferation of mature megakaryocytes with characteristic morphology (increased numbers, large/hyper-lobulated nuclei, loose clustering) to distinguish ET from reactive thrombocytosis and pre-fibrotic myelofibrosis, plus

- Not meeting WHO criteria for BCR-ABL1+ chronic myeloid leukemia, polycythemia vera, primary myelofibrosis, myelodysplastic syndromes, or other myeloid neoplasms, plus

- Clonal marker (JAK2, CALR, or MPL mutation)

- Minor:

- Presence of a clonal marker or absence of evidence for reactive thrombocytosis

Clinical Presentation:

- Asymptomatic: Thrombocytosis is common (incidental laboratory finding)

- Symptoms: When present may include fatigue, insomnia, migraines, headaches, burning skin, dizziness and splenomegaly

- Thrombotic events: May also include risk for stroke, myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, and/or splanchnic vein thrombosis, which is the principal cause of morbidity and mortality

- Bleeding: Particularly with extreme platelet counts (>1,000×109/L) and acquired von Willebrand factor deficiency. Over time, a minority progress to myelofibrosis or acute leukemia

Treatment Goals:2

- Prevent thrombosis and major bleeding

- Control symptoms (microvascular and constitutional) and manage splenomegaly

- Minimize disease progression and treatment toxicity

- Individualize therapy by thrombotic risk, mutation status, comorbidities, and patient preference

Current Treatment Landscape:5,6,7

- Low-dose aspirin (75–100 mg daily) is recommended for most patients unless contraindicated (e.g., high bleeding risk or acquired von Willebrand disease)

- Address cardiovascular risk factors (BP, lipids, diabetes, smoking cessation) and treat reversible causes of thrombocytosis (e.g., iron deficiency) where appropriate

- Cytoreductive therapy (indications): Indicated for high-risk patients (age >60 and/or prior thrombosis) and for selected low-risk patients with extreme thrombocytosis, microvascular symptoms refractory to aspirin, or other high-risk features

- First-line options:

- Hydroxyurea (HU): Oral, widely used as first-line cytoreduction in high-risk ET

- Interferon-alpha (pegylated forms; ropeginterferon alfa-2b): Preferred in younger patients and during pregnancy due to non-teratogenic profile and potential ability to reduce mutant allele burden

- Anagrelide: A platelet-lowering agent used as an alternative to hydroxyurea, but comparative data have raised concerns about cardiovascular/safety profiles versus HU in some studies

- Second-line/Special Scenarios:

- Switch therapy: HU intolerance/resistance (e.g., to interferon or anagrelide)

- Pregnancy: interferon-alpha is preferred for cytoreduction; aspirin management individualized

- First-line options:

Supportive Care & Monitoring:

- Serial CBC and clinical assessment for thrombosis/bleeding symptoms, side effects, and transformation

- Bone marrow biopsy when disease course is atypical or fibrosis/transformation is suspected

Conclusion:

Essential thrombocythemia is a clonal MPN hallmarked by sustained thrombocytosis and a variable clinical course dominated by thrombotic risk and, less commonly, bleeding or progression to MF/AML. Contemporary diagnosis relies on platelet thresholds, bone marrow morphology, and molecular testing (JAK2/CALR/MPL) to exclude reactive causes and pre-fibrotic myelofibrosis. Risk-adapted therapies, principally low-dose aspirin and cytoreduction for high-risk patients (hydroxyurea or interferon), can reduce thrombotic complications and address symptomatic burden.

References:

- Tefferi A. Essential thrombocythemia: 2024 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2024.

- Ashorobi D, Gohari P. Essential Thrombocytosis (Essential Thrombocythemia, ET). PubMed. Published 2020.

- Alvarez-Larrán A, et al. Application of IPSET-Thrombosis in large ET cohorts. Blood/BMJ analyses. 2023.

- Barbui T, et al. WHO diagnostic criteria & value of bone marrow biopsy in ET. Leukemia/WHO publications.

- Cattaneo M. Aspirin in essential thrombocythemia: for whom? Haematologica/Reviews. 2023.

- Kiladjian JJ, et al. ROP-ET / ropeginterferon alfa-2b trials in ET. Blood/ASH abstracts, 2024–2025.

- Park YH, et al. Hydroxyurea vs anagrelide experience and combination strategies. J Clin Med. 2024.

*Information presented on RxTeach does not represent the opinion of any specific company, organization, or team other than the authors themselves. No patient-provider relationship is created.