Pediatric and Adolescent Obesity

In January 2023, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) released the first edition of the Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents with Obesity. We are here to summarize the highlights for you!

In January 2023, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) released the first edition of the Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents with Obesity. This document provides us with “a more complete understanding of the issues, factors, and needs of patients combating overweight and obesity, as well as successful treatment options to assist them in their battle.”

In this RxTeach post, we are going to cover some of the highlights and information I found most interesting. Let’s dive right in!

It is estimated that 14.4 million children and adolescents are affected by obesity. The time has come to finally address this chronic disease, the short- and long-term consequences of obesity, and stop assuming these patients will “outgrow” their childhood weight. Childhood obesity is often defined as a BMI of ≥95th percentile for age and sex. In addition, obesity prevalence increases with increasing age, so it is of utmost importance to start treatment as early as possible.

I want to make it clear that “treatment” does not imply pharmacologic therapy. Treatment, in this guideline, pertains more to behavioral strategies and recommendations. We will discuss treatment in more detail later in this post.

Another critical statement included early in the document is as follows:

- "Pediatricians and other [health care professionals] have been—and remain—a source of weight bias. They first need to uncover and address their own attitudes regarding children with obesity. Understanding weight stigma and bias, and learning how to reduce it in the clinical setting, sets the stage for productive discussions and improved relationships between families and pediatricians or other [health care professionals]. Acknowledging the multitude of genetic and environmental factors that contribute to the complexity of obesity is an important mitigator in reducing weight stigma."

I think the above statement is so important! As health care professionals, we have to be unbiased in the treatment of our patients. We need to reflect on our own internal thoughts about this population, and work through our personal biases first, prior to providing advice and treatment.

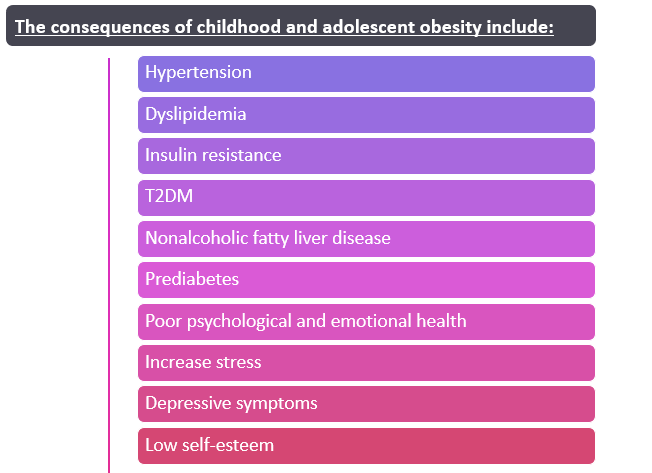

Despite needing to reflect our own attitudes toward the overweight and obese population, there are significant health ramifications if pediatric and adolescent patients are left uneducated and untreated (see figures below).

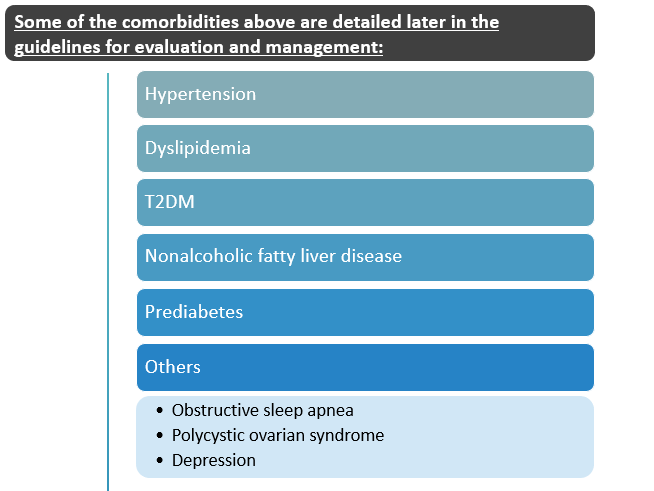

And for those of you interested in learning more, only a few disease states are further explained in the guidelines:

With specific recommendations outlined and clarified in this document, practitioners now have more clear and direct guidance towards treating these diseases in the younger population!

The AAP places heavy weight on the risk factors associated with childhood and adolescent obesity. This is especially important for us to know as healthcare workers. We can identify patients who may be at increased risk and provide counseling to the parents. We can also discuss various options with the parents or caregivers if they are struggling with providing healthy, nutritious food options for their children.

There are numerous risk factors that are listed in the guidelines. I put an emphasis on "numerous" because there are 40+ listed. The risk factors are separated into four digestible categories:

- Policy Factors (i.e. marketing of unhealthy foods)

- Neighborhood and community factors (e.g. lack of fresh food access, proximity of fast food)

- Family and home environment factors (e.g. parenting feeding styles, snacking behaviors, psychological stress)

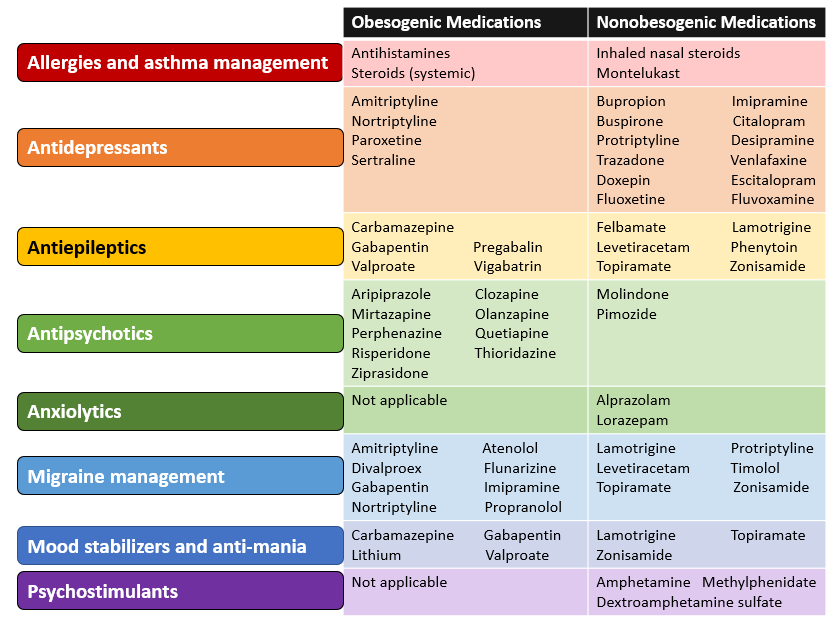

- Individual factors (e.g. genetic factors, birth weight, mental illnesses and medication use)

For medication use, the AAP provides a table of obesogenic medications to be aware of and a list of nonobesogenic medications that could be considered as alternatives if an appropriate situation were to arise for a switch. I re-vamped and color-organized their table below!

Outside of the medication table, I wanted to chat about Tables 18 and 19 in the guidelines. I particularly found these "tables of strategies" eye-opening. Of course, seeing as we are in 2023 and technology is omnipresent, some of these recommendations come with no surprise. It is still baffling (in my opinion) that we have to have specific guidance written on some of these topics!

Table 18: Behavior Strategies

(those re-endorsed by major professional and public health organizations)

1. Reduction of sugar-sweetened beverages

- AAP states fruit juice is a poor substitute for whole fruit; advocates eliminating fruit juice in children with excessive weight gain.

2. Choose my plate

- AAP includes this as a way to provide more balanced, low sugar, low concentrated fat, nutrient dense meals.

3. 60 minutes daily of moderate to vigorous physical activity

- Aerobic exercise in (specific) 60 minute intervals has been shown to improve body weight in children. However, in my opinion, 60 minutes every day can be very difficult to achieve for any individual, not just children! And 60 minutes at one time is even more difficult. As much as I love this recommendation (as I live a very active lifestyle), I do not see it as a very feasible one to implement.

4. Reduction in sedentary behavior

- “Reduction in sedentary behavior, generally defined as reduced screen time, has consistently shown improvement in BMI measures. The AAP recommends no media use under age 18 months, a 1 hour limit for ages 2–5 years, and a parent-monitored plan for media use in older children, with a goal of appropriate, non-excessive use but without a defined upper limit.”

Table 19: Common Strategies

(these are common but not addressed by the AAP or other major health organizations; systematic reviews have provided information about potential benefits as well as harm or lack of harm)

1. Avoidance of breakfast skipping

- This eating approach divides foods into the colors of a traffic light. Green for low-calorie foods, yellow for moderate calories, and red for high-calorie foods.

3. "5 2 1 0"

- Each component of 5-2-1-0 messaging aligns with a major recommendation or guideline: 5 fruits and vegetables a day is consistent with the USDA Choose MyPlate recommendations, 2 hours or less of screen time is consistent with earlier versions of AAP policy; 1 hour or more of moderate to vigorous physical activity is consistent with Physical Activity Recommendations for Americans, and 0 (or nearly no) sugar-sweetened beverages aligns with USDA, AHA, and AAP.

4. Use of screen-based physical activity (exergames)

- Exergames consist of video games that require physical activity to play (i.e. Just Dance on the Nintendo Wii, Dance Dance Revolution on the PlayStation or Xbox, Pokémon Go on iOS and Android, etc.).

5. Appropriate amount of sleep for age

- Obesity is associated with shorter sleep duration due to increased calorie consumption and potential hormonal and metabolic alterations such as increased ghrelin and decreased leptin leading to hunger.

This guideline does not cover the prevention of obesity, but the AAP mentioned they will address this in a forthcoming policy statement.

This guidance document does contain recommendations for children with special health care needs. They briefly address:

- Hyperphagia

- Prader Willi Syndrome

- Hypothalamic obesity

- ADHD

Medications discussed for the treatment of obesity and their mechanisms of action (page 61) are below:

Metformin

- Antidiabetic agents used in T2DM in patients 10 years and older. This is not approved as a weight loss drug. Studies have shown a BMI reduction of 1 kg/m^2 at a dose of 1000 mg BID for 6 months in addition to adjunct lifestyle treatment in children and adolescents 6 years and older.

Orlistat

- Intestinal lipase inhibitors that blocks fat absorption through inhibition of pancreatic and gastric lipase. Approved for children 12 years and older. Usually dosing is 120 mg 3 times per day. It is uncommonly used in the pediatric population due to fecal urgency, steatorrhea, and flatulence.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist

- Decrease hunger by slowing gastric emptying and acting on targets in the central nervous system. Studies have shown a BMI reduction of 5%. Exenatide is approved for children 10-17 years of age with T2DM. Liraglutide is approved for treatment of obesity in children 12 years and older with or without T2DM.

Melanocortin 4 receptor agonists

- Act on the MC4R pathway to restore normal function for appetite regulation that has been disrupted because of genetic deficits upstream of the MC4 receptor. This receptor in the brain regulates hunger, satiety, and energy expenditure. When used appropriately, a dose of 1 to 3 mg daily subcutaneously results in weight loss of 12%-25% over 1 year. Setmelanotide is FDA approved for patients 6 years and older with pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) deficiency, proprotein subtilisin or kexin type 1 deficiency, and leptin receptor deficiency confirmed by genetic testing.

Phentermine

- Central norepinephrine uptake inhibitor but also non-selectively inhibits serotonin and dopamine reuptake and reduces appetite. This is approved for short course therapy (3 months) for adolescents 16 years or older.

Topiramate

- Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor and suppresses appetite centrally through largely unknown mechanisms. This is a potential teratogen and requires counseling and reliable birth control for patients able to become pregnant. Has an indication for treatment of binge eating disorder in adults 18 years and older. There is only 1 study evaluating the use of topiramate in children for binge eating and it did not differ from placebo. It is approved for children 2 years and older with epilepsy and headache prevention in children 12 years and older.

Phentermine and topiramate

- As a combination, this medication is approved for weight loss in adults, and recent data shows that in patients 12-17 years of age with a documented history of failure to lose sufficient weight or failure to maintain weight loss, BMI percent change was -10.44 and -8.11 compared with placebo.

Lisdexamfetamine

- Similar in mechanism to phentermine, it is a stimulant-class medication approved for children 6 years and older with ADHD. It does have an indication for treatment of binge eating disorder in patients 18 years and older, and therefore, it is used off-label for children with obesity. There is no evidence available to support efficacy and safety in this population at this time.

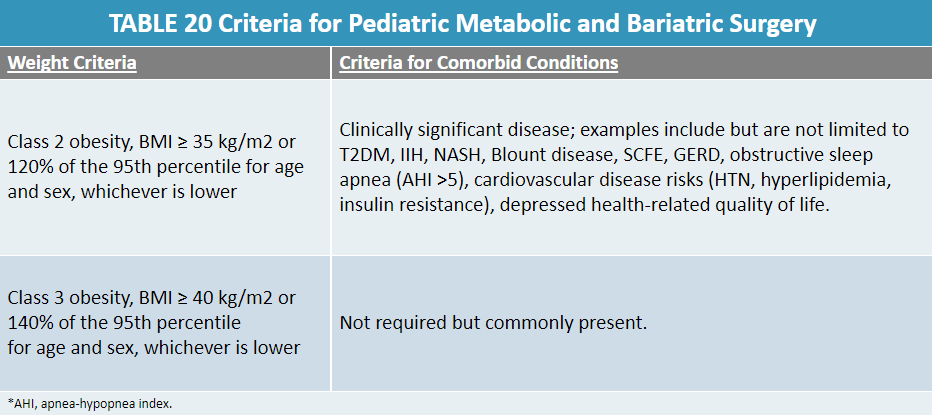

Believe it or not, children can undergo bariatric surgery. The specific criteria outlined in this guidance document is found in Table 20:

Noted evidence gaps and directions for future research:

- Duration of treatment effects

- Heterogeneity of treatment effects and special populations

- Limited understanding of specific components, dose, duration

What do you think of the new Pediatric and Adolescent Obesity Guidelines? What questions do you currently have? Drop a comment below!