The New Food Pyramid

The new dietary guidelines are an incredible improvement upon the previous version of the food pyramid.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Agriculture recently released a new set of dietary guidelines. Many Americans are skeptical of the guidelines, particularly because of the personal habits of Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. In a recent interview, Kennedy claimed he was on the carnivore diet, which consisted strictly of meat and ferments. You can read about my personal experience with the carnivore diet here.

Despite the controversial views around RFK, I'm here to tell you that the new dietary guidelines are an incredible improvement upon the previous version of the food pyramid. There are still some recommendations in the guidelines that I would caution you against; however, if all Americans followed these guidelines, we would be a significantly healthier country. Let's dive into the new recommendations in detail and discuss the pros and cons.

We will focus on the recommendations for healthy adults. There are additional sections regarding pediatrics, pregnant women, and other groups, which we will cover in future articles.

Firstly, these guidelines are relatively straightforward. The entire section on healthy adults is only 4 pages long, and the recommendations are pretty high-level.

The guidelines begin by acknowledging that the correct number of calories will vary from person to person, depending on size and other factors. Larger, more muscled individuals will require more calories to maintain their weight, while smaller, lighter individuals will generally require less, depending on the amount of physical activity in each. They also immediately suggest drinking water (still or sparkling) over sweetened beverages. This is a great start. Remember that a can of Coke has 14o calories, all of which come entirely from the 39 grams of sugar packed into the can. Cutting out 1 soda per day would immediately decrease weekly calorie consumption by 980 calories!

The guidelines then go on to prioritize protein with every meal. At RxTeach, we have been promoting the benefits of protein for years. See one such article from 2022 regarding the incredible benefits of protein consumption below.

Regarding protein, the guidelines recommend consuming a variety of animal sources (eggs, poultry, seafood, red meat) and plant sources (beans, lentils, legumes, nuts, seeds, soy). So no recommendations for the carnivore or vegetarian diets, which I ultimately agree with. They also promote specific cooking methods, including baking, broiling, roasting, stir-frying, or grilling. Essentially, any cooking method aside from deep frying.

In an effort to prevent increased consumption of processed meats (think roller-grill taquitos at the gas station), the guidelines recommend choosing meats with little to no added sugars, refined carbohydrates, starches, or chemical additives, and to flavor them with salt, spices, or herbs based on personal taste.

They also recommend a daily protein intake of 0.54 - 0.73 grams per pound of body weight, adjusted to your individual calorie needs. For context, the recommended daily amount (RDA) of protein before these guidelines was 0.36 grams per pound, so this is a doubling of the previous RDA. I'm a huge fan of this change, particularly for non-sedentary adults (which we should all strive to be). For any of our highly active readers, I recommend staying on the high end of this range and even eating up to 1 gram per pound if maintaining or building muscle is particularly important to you.

Protein is the primary structural component of your skeletal muscle, among many other biological structures in your body. Protein also has a relatively low caloric footprint. At 4 calories per gram, it's almost half as calorie-dense as fat (9 calories per gram). Although it's calorically equal to carbohydrates (also 4 calories per gram), it has an important separator: thermic effect. Put simply, the thermic effect of food is the calorie requirement needed to actually metabolize the food you eat. In this case, if you eat 100 calories worth of protein, between 20 and 35 calories will be burned to digest it. So your net consumption is only 65-80 calories. Pretty cool.

The guidelines then go on to suggest dairy consumption, which is where my personal recommendations and eating habits no longer align. The new guidelines specifically recommend consuming full-fat dairy with no added sugars because of its protein, healthy fat, vitamins, and mineral content. They also recommend 3 servings per day as part of a 2,000-calorie dietary pattern.

Here's a question for you. What is a "serving"? Does anyone know? It's one of my least favorite units because it's not uniform and depends entirely on what you're eating in the first place. Regarding dairy, 1 "serving" would be equivalent to 1 cup of milk, yogurt, or fortified soy milk, 1.5 oz of hard cheese, or 2 oz of processed cheese. However, 1 "serving" of pizza is equivalent to 1 "slice". How big is a slice? What if I'm eating square-cut pizza or deep dish pizza? It's a stupid system.

My issue with the dairy recommendation is that full-fat cheese and milk have a serious consequence: calorie density. It is so easy to eat 2 oz of Parmesan cheese (especially when added to other foods) or drink a glass of red cap milk. They also taste amazing. Listing these items as "healthy" could cause some Americans to overconsume dairy and consequently fall into a caloric surplus. Of course, that would require Americans to actually attempt to follow the recommendations in the first place, which almost no one will. I don't personally see any issues with 2% or skim milk and fat-free Greek yogurt. They are still high in protein and minerals while being significantly lower in calories.

We then pivot to what everone thinks of when they imagine "healthy" food. The guidelines recommend eating a wide variety of colorful, nutrient-dense vegetables and fruits, prioritizing whole foods in their original state and washing thoroughly before eating or cooking. Frozen, dried, or canned options with little to no added sugar are considered acceptable. Juice should be limited or diluted with water, and for a 2,000-calorie diet, aim for about 3 servings of vegetables and 2 servings of fruit per day (again with servings, ugh.)

These are great recommendations. I'm no vegetarian, believe me, but it is nearly impossible to argue against the benefits of fruit and vegetable consumption. Fruit tastes great on its own, and with some practice, you can make vegetables taste incredible too. Both are also generally lower-calorie and relatively filling due to their fiber content. As long as you're hitting your protein, it's difficult to overeat fruits and vegetables, so have at it!

The next 2 sections are some of the most controversial, as these areas have seen some of the worst recommendations in the past. I am referring, of course, to fats and grains.

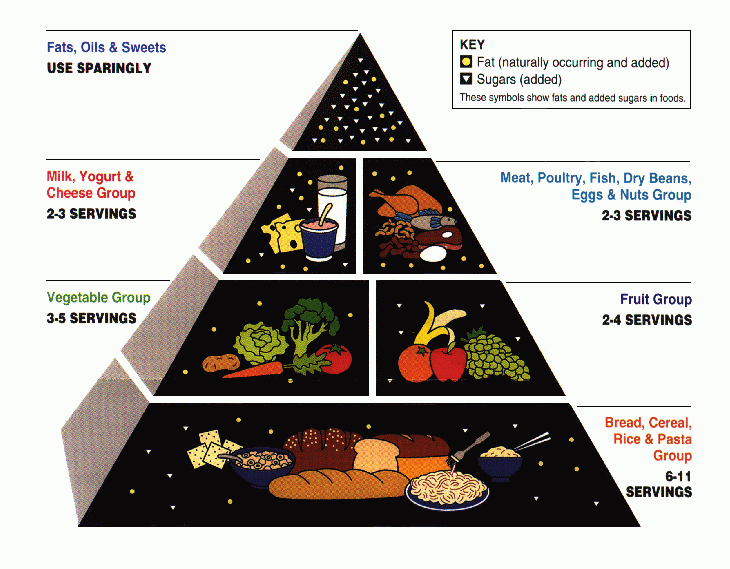

The USDA Food Pyramid looked like this from 1992 to 2005, and this is where a lot of anger and frustration over previous recommendations comes from.

As you can see, the lion's share of Americans' calories was supposed to come from processed carbohydrates, according to our government. Some would argue this partially led to the diabetes epidemic in the United States. Few methods will more effectively trample your insulin sensitivity than a diet consisting mostly of processed carbohydrates. I wish this weren't the case, as I would love to eat mostly bagels and pasta, but it's true.

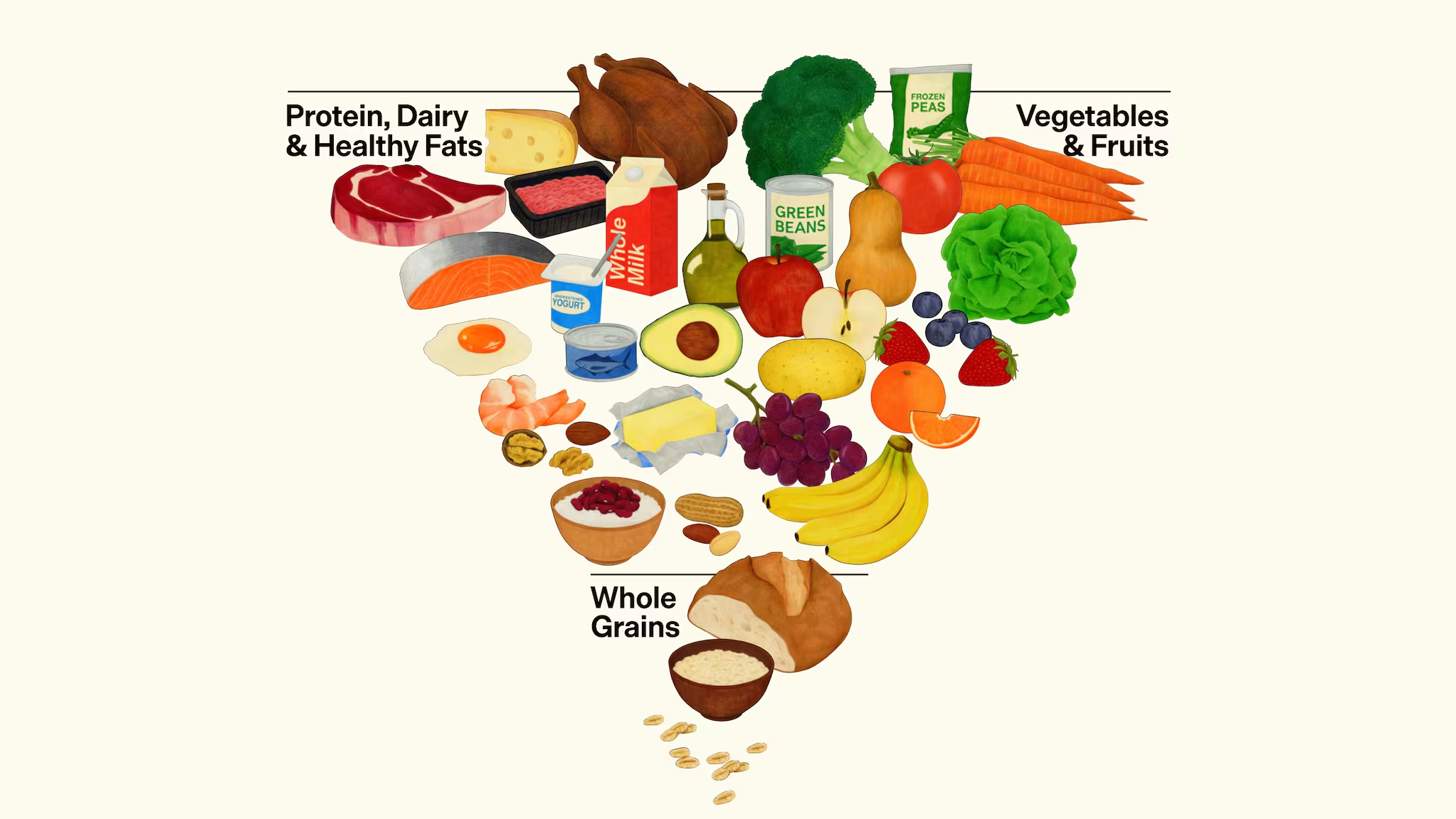

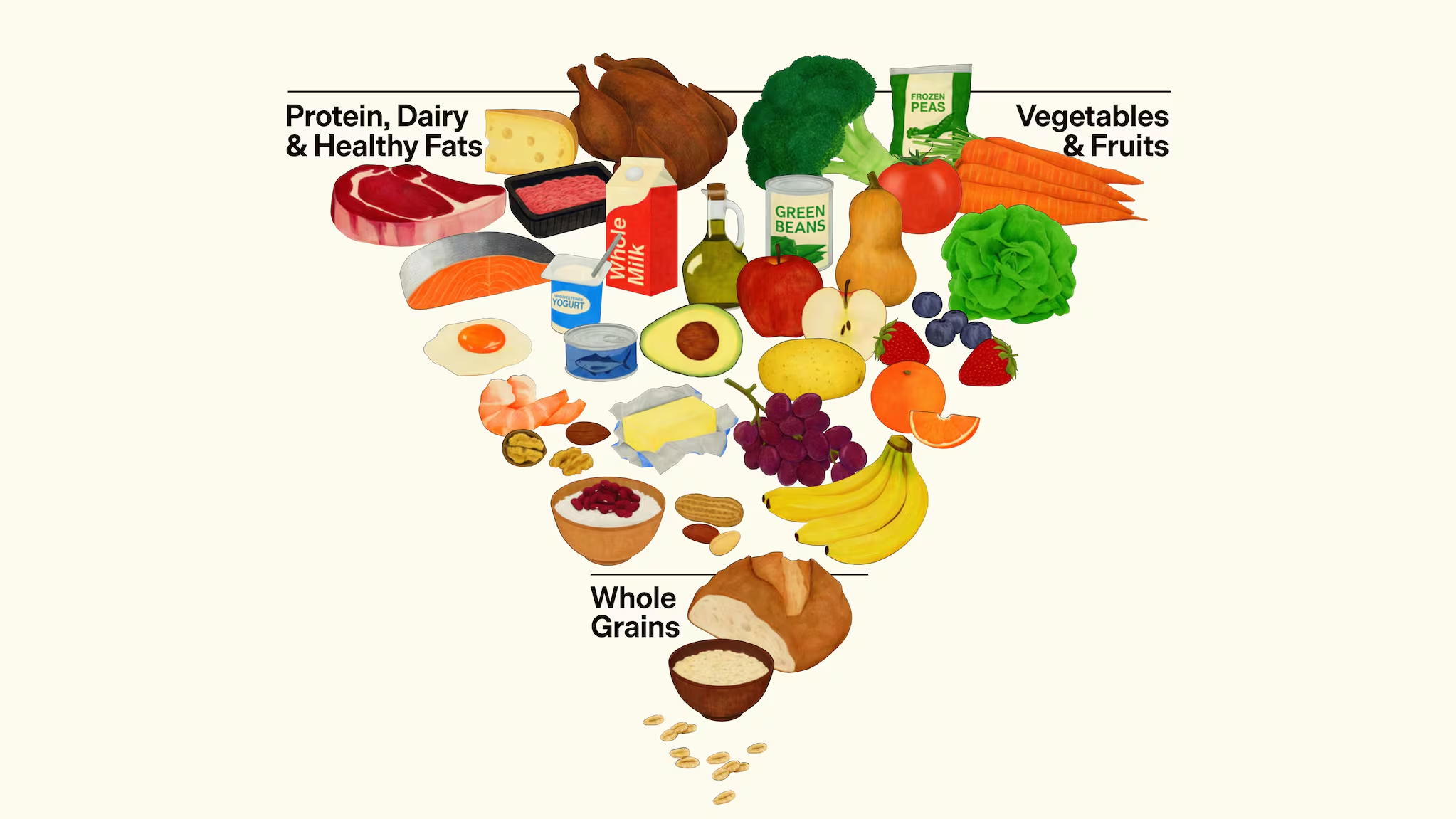

Let's compare this to the new pyramid, which for some reason, they decided to show upside down (perhaps because Stranger Things became so popular).

As you can see, grains (specifically whole grains) are now the smallest recommended food group. This showcases a fundamental shift in nutrition recommendations from the US government, and one that I agree with. The new recommendation is to "significantly reduce the consumption of highly processed, refined carbohydrates, such as white bread, ready-to-eat or packaged breakfast options, flour tortillas, and crackers."

There is, of course, room for nuance. If you are training for a marathon or other long-distance endurance event, you should absolutely consume a larger percentage of carbohydrates to fuel your training. Ideally, these will not be "ultra-processed", but if you aren't getting in your slice of sourdough or oatmeal before your long runs, your training will be less effective. Most Americans will never even consider running a marathon, so this is a niche recommendation.

Another major shift is the prioritization of healthy fats. The guidelines recommend healthy fats from whole foods such as meats, eggs, omega-3–rich seafood, nuts, seeds, full-fat dairy, olives, and avocados. For cooking, prioritize using oils rich in essential fatty acids such as olive oil (with butter or beef tallow as alternatives). They do recommend keeping saturated fat under 10% of total daily calories by limiting ultra-processed foods, and note that more high-quality research is still needed on optimal fat types for long-term health.

Again, this is a major shift in the pyramid. Fats went from the least recommended food group to an essential one. However, I would add significant caution to this recommendation. Fats and oils are incredibly high in calories. Yes, there are many health benefits to consuming these fats; however, they would all be negated by eating too many calories. Don't make that mistake. The key is a balanced approach of protein, carbs, and fats while maintaining a calorie deficit (if losing weight) or being at maintenance calories (if maintaining weight).

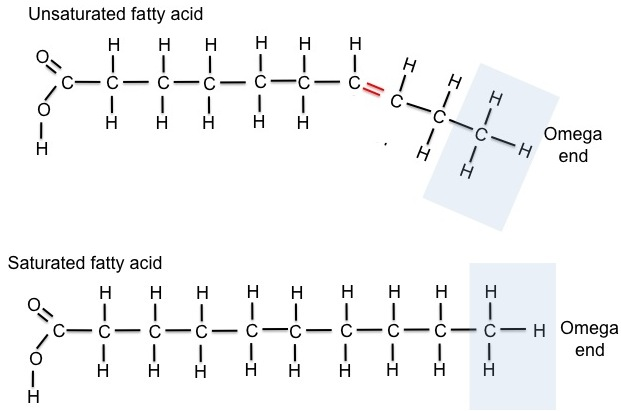

Regarding saturated fat, which mostly comes from foods like red meat (beef, pork, lamb), full-fat dairy products (butter, cheese, cream, ice cream), and tropical oils (coconut, palm, and palm kernel oil), I think the 10% rule makes sense. There is evidence to suggest that even in the context of low-carbohydrate consumption, high saturated fat diets can still increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. As a reminder, saturated fats are solid at room temperature while unsaturated fats are liquid. This is due to the double bond(s) present in unsaturated fatty acids, such as omega-3 (EPA and DHA in fish oil) and omega-6 fatty acids.

Not mentioned in the recommendations are seed oils. Remember, only olive oil, butter, and beef tallow (despite being high in saturated fat) were recommended. You can see our previous article regarding seed oils below. Generally speaking, seed oils can be a part of a healthy diet when consumed in moderation, like most things. However, they too are very calorie-dense (like whole-fat products), so use caution.

The last sections of the guidelines cover the new boogeymen of nutrition: highly processed foods, added sugars, refined carbohydrates, and alcohol. The recommendations are to avoid highly processed, salty or sweet packaged foods and sugar-sweetened beverages, and instead prioritize nutrient-dense, home-prepared meals and healthier options when dining out.

They also recommend limiting artificial additives and non-nutritive sweeteners (including artificial sweeteners such as sucralose and aspartame), and keeping added sugars as low as possible (no more than 10 grams per meal). This is all fantastic advice, though I don't see much threat in artificial sweeteners at this time. I don't think the occasional Diet Coke is going to do you any harm given what we know about aspartame. I actually think it's better than consuming calorie-dense drinks like the original, sugar-packed Coca-Cola. In the US, overconsumption of calories, rather than any specific ingredient or additive, is the main issue causing diabetes, CVD, and ultimately death.

Regarding alcohol, the guidelines simply recommend consuming less. Boring, but fair enough.

In conclusion, eat a balanced diet, prioritize protein, eat less prepackaged food, and cook more at home. That's it! Mix it up and try new foods from time to time. Remember, eating food with friends and family is one of life's greatest joys, so my last recommendation is to eat with others!

*Information presented on RxTeach does not represent the opinion of any specific company, organization, or team other than the authors themselves. No patient-provider relationship is created.